The Rise of Courtly Love

Geoffrey of Monmouth set the stage for Arthur and his knights to become famous throughout the world. But Geoffrey's History was still largely a military history. In the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, two major events took place which would shape the Arthurian saga for centuries to come.

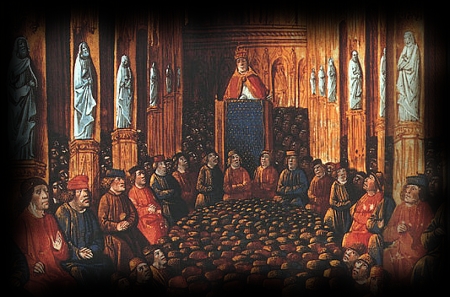

Pope Urban II presiding over the Council of Clermont. From an illuminated manuscript c. 1490.

Pope Urban II presiding over the Council of Clermont. From an illuminated manuscript c. 1490.

The first of these events was that in the mid–eleventh century, hordes of invaders known as Seljuk Turks overran Central Asia, and took many territories from the Byzantine Empire. In its heyday, the Roman Empire had controlled almost all of Eastern and Western Europe, extending into portions of Asia Minor and the Middle East. When the empire fell, Western Europe was overrun by invaders, and plunged into primitive conditions, with each territory being controlled as its own sort of city–state. The Eastern portion of the empire, by contrast, which included much of Eastern Europe and Asia Minor, remained strong, and continued to flourish as a center of trade for the Old World. This empire later came to be known as the Byzantine Empire.

During the early days after the fall of the Roman Empire, Christianity had been divided into two sects, with the pope in Rome presiding over the Roman Catholic Church in Western Europe, and the emperor in Constantinople (present–day Istanbul) presiding over the Greek Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire. The Holy City of Jerusalem was considered sacred by Muslims, Jews, and Christians. Ever since 638 A.D. the city had been ruled by Muslim authorities, but they were tolerant of Christians and Jews, and allowed both to live there, and to make pilgrimages to the city.

In 1095, Muslim rulers known as Fatimids expelled Christians from Jerusalem, and began persecuting any Christians who made pilgrimages to the city. Alexius I Comnenus, the emperor of the Byzantine Empire, sent an urgent plea to the Pope, asking him for reinforcements to help fight off the invading Seljuk Turks, and describing how Christians in the Holy Land were being slaughtered.

On November 27th, 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II called out for Christian forces to rise up and take back the holy city. As a reward for serving the Church, he said, every person who embarked on the quest would have his land and property protected, and would be guaranteed a place in Heaven. This launched the First Crusade, the first in a succession of battles which would be fought for control of Jerusalem over the next 200 years.

For the next 200 years, a series of nine crusades would ensue, with neither side successfully maintaining control over Jerusalem. Each crusade typically lasted many years, and many knights either died in the Holy Land, or settled down to start families there. The knights who did choose to return home typically didn't make it back until they were old men. The Arab world already had a longstanding tradition of love poetry involving the sacrifices a man would make for his lady. Some historians believe that these stories were carried back by knights who fought in the crusades, and that they lent themselves to shaping the tradition of courtly love in medieval Europe.

One of the few contemporary depictions of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

One of the few contemporary depictions of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

The second major event was that Eleanor of Aquitaine was born. Eleanor of Aquitaine was a fiercely–independent woman, and a powerful force in her own right. In an era which expected women to be meek and subservient to their husbands, Eleanor broke all the rules. She defied her husband's orders by going on the Second Crusade dressed in full battle armor; she ruled as queen of both England and France during her lifetime; and she waged war against one of her husbands. On the one hand, medieval French society had the Christian Church teaching that women were to be submissive to their husbands. On the other hand, France's own ruler was a powerful and independent woman. French society had to come to terms with this discrepancy, and the way it did this was in the ideal of the Lady.

Whereas women had previously been depicted in medieval literature as only being useful for marriage in order to gain political leverage, the Lady was someone to be looked up to and respected. Knights were expected to fight battles in defense of their lady's honor, and to go on great quests to prove their worthiness to marry her. The Lady also had her own power. She could either accept or reject a knight's advances, and many poems from this time depict the struggles a knight would endure in order to win his lady's heart. While knights were portrayed as having brute strength, ladies were depicted as having an undefinable, mystical power. Literature from this period frequently depicts ladies possessing magical talismans or potions which they provide to their knights to help them on some valiant quest.

At the same time, the Church was also struggling to maintain control over the knights, who, in the Church's view, had become too powerful. A code of conduct known as "chivalry" emerged, whereby knights were only allowed to fight on certain days, and were expected to defend their ladies and the Church.

As historian Geoffrey Ashe explains, medieval people viewed the Arthurian romances of this period similarly to the way American audiences view an Old Western movie: that is, they understood the stories were fictitious, but they also understood that they were partly based on a real period in time which really did pass. Historian Eileen Power takes this a step further, by comparing women's views of the courtly romances to the way a modern woman views a romance novel: the material is reflective of the events taking place in her society, but it's also something unrealistic, which she reads when she needs an escape from the day.

Nowhere is the tradition of courtly love stronger than in the writings of Chrétien de Troyes. Chrétien de Troyes was a poet of the late twelfth century. Little is known about the man himself, although some historians have speculated that he may have been a cleric or nobleman. Whoever he was, he left us with five poems which played a pivotal role in shaping medieval literature.

Unlike his predecessors, Chrétien's writing was not about Arthur, but about his knights. Arthur is depicted as a kindly, old king who rules over Camelot while his knights go on valiant quests in search of magical treasures, or in defense of their ladies. Writing for Marie de Champagne, one of the daughters of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Chrétien's writing deals with matters of the heart, as opposed to military history. Even when translated into modern English, his poems are considered by many to be among the most beautiful poetry ever written. For instance, consider the following passage taken from his poem Yvain: The Knight of the Lion:

"What a fool I am, to want

What I'll never have. Her lord

Is dead of his wounds, and can I

Believe in peace between us?

By God, I understand nothing!

She loathes me, now, and not

For nothing, and not wrongly.

But 'now' is the crucial word,

For a woman's mind has a thousand

Directions. And perhaps that 'now'

Will change. Oh, surely it will change,

And how stupid of me to stand here

Lost in despair. God grant

That she changes soon! For Love

Has decided to put me forever

In her power, and Love takes what it wants!

Not to accept Love's wish

When Love comes, and Love asks, is more

Than wicked, it is treachery. And I say,

And whoever worships Love

Let him listen, that a deserter from Love

Deserves no happiness. I may lose,

But I'll always love my enemy.

How could I ever hate her,

If I wish to be loyal to Love?"

(Chrétien, pp. 45)

Chrétien's writing quickly became popular, and spread across medieval Europe. He is the first to introduce both the character of Lancelot, and Arthur's kingdom of Camelot. His poem Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart details Lancelot's quest to save the queen when she is abducted by Arthur's enemy, Meleagant, and is the first to introduce the forbidden love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere. To this day, Chrétien de Troyes is considered to be among the most influential writers to shape the Arthurian Legend.

The theme of courtly love is central to the mythology surrounding King Arthur and his knights. But while the writings of Chrétien de Troyes were largely innocent, and dealt with matters of the heart, other events were unfolding in medieval Europe which would take the Arthurian Legend in a more sectarian direction.