King Arthur:

An Introduction

We've all heard of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. But who was Arthur? Was he a real person? And what was the Round Table? What follows is an overall summary of three major aspects of the legend.

The Legend

In legend, Arthur was the high king of the Britons who united them and drove the invading tribes of

Saxons, Angles, and Picts from their shores. He was the son of Uther Pendragon and Ygraine, the Duchess

of Cornwall. Uther was helplessly in love with the Duchess, but she was married to Duke Gorlois. Uther

used magic to make himself resemble Gorlois, and entered the Duchess' bed chamber, where Arthur was

conceived. Afterwards, Uther's forces killed the Duke, and he took Ygraine as his wife.

In legend, Arthur was the high king of the Britons who united them and drove the invading tribes of

Saxons, Angles, and Picts from their shores. He was the son of Uther Pendragon and Ygraine, the Duchess

of Cornwall. Uther was helplessly in love with the Duchess, but she was married to Duke Gorlois. Uther

used magic to make himself resemble Gorlois, and entered the Duchess' bed chamber, where Arthur was

conceived. Afterwards, Uther's forces killed the Duke, and he took Ygraine as his wife.

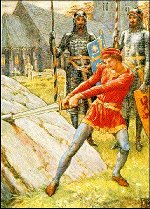

The king became sick, and Arthur was raised in secret by Sir Ector, a loyal ally of the king's. When he was fifteen, he proved his right to rule Britain by pulling the famed sword from the stone in a churchyard in Westminster.

As king, he united Britain and drove off the invaders from the land. His kingdom was called Camelot, and his coat of arms was the red dragon. His wizard was Merlin, his queen, Guinevere, one of the most beautiful women in the kingdom. He received his sword, Excalibur, from the Lady of the Lake, a magical creature who made her home underwater.

Under Arthur's rule, the Knights of the Round Table were formed, an order of knights whose charge it was to defend Camelot and her ladies. At the Round Table, all knights sat together as equals, and discussed how to best protect the kingdom.

Arthur's best friend was his finest knight, Sir Lancelot, whose son, Galahad, obtained the Holy Grail. Lancelot was denied the Grail because he was secretly in love with Arthur's queen, Guinevere. When their love affair was exposed, a bitter war broke out between the two men, with Arthur pursuing Lancelot all the way to France.

In Arthur's absence, his kingdom was taken over by Mordred, his nephew–son and a product of incest and deception by his half sisters Morgause and Morgan le Fay. Arthur and Mordred both slew one another while battling for the kingdom. Afterwards, Arthur was taken to the magical island of Avalon to be cured of his wounds. Some say he still lies there, sleeping until such time as Britain has need of him again.

The History

The earliest tales about King Arthur were much different than the modern legend has come to be understood today. No one knows whether Arthur was a real person, but the earliest written records say that he was a fifth or sixth century king who defended Britain from invading tribes of Saxons, Angles, and Picts.

Britain during this time was a far cry from the secure, stable country it is today. The Roman Empire had ruled the southern half of the island since 43 A.D. But in the fifth century, the Empire withdrew, and the last remaining militia had been sent to the Continent in a failed attempt to wage war on Rome. The people of Britain, once prosperous Roman citizens, were now left open to attack from all sides, and their civilization and way of life quickly crumbled.

The earliest legends of Arthur say that he was not a king, but a military commander who, for a time, helped to organize the Britons, and led several successful battles against the invaders, who now pounced on them from every direction.

The Literature

With the majority of the population illiterate, tales of Arthur and his knights were spread largely by word of mouth for the next several centuries. As his legend grew, it quickly adopted aspects of other folklore, and the superstitious people of the time began to associate it with more fanciful tales of giants and magic.

Medieval culture did not have the same appreciation for historical accuracy that we have today, and as authors retold the tale in their own time, Arthur gradually came to be made into a king, and his men into knights of nobility. Arthur's popularity exploded in the 1100s when Geoffrey of Monmouth published his History of the Kings of Britain, claiming it was a genuine history, when in reality it was a collection of distorted folklore, or tales made up by Geoffrey himself. The book placed Arthur at the center of its climax, and portrayed him as a great king ruling over a mighty empire.

With the rise of courtly love, his legend came to be associated with courtly romance, as opposed to tribal warfare. A blend of largely–inflated tales kept alive by word of mouth, courtly love, superstition, and a short revival of Pagan folklore, all combined to cause the legends to take on their own unique quality, a combination of tragic romance and mythical folklore.

If the real life Arthur could see the legend today, he would doubtless be amazed at how different it is from the real history. Yet the legend continues to endure and remain in the hearts and minds of the people, as it has done for more than a thousand years.